Why the Long Face?

Jaws drop in amazement at the new Theatre at Great Canadian Casino Resort Toronto

Story: Ian VanDuzer

Photography: Walters Group

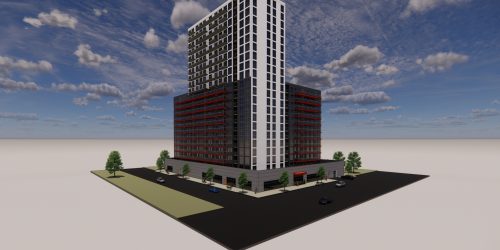

When the Great Canadian Gaming Corporation took ownership of the Woodbine Casino – attached to Toronto’s most-established horse racing track – they came with a new vision of building an entertainment mecca close to North America’s fourth largest city.

Taking inspiration from successful Vegas complexes, the new Great Canadian Casino Resort Toronto is not just a casino: it’s also two hotels, a spa, and a 5,000 seat Theatre that’s already hosted Gwen Stefani and Blake Shelton.

A part of the ambitious $1 billion expansion, the Theatre is a spectacular venue with a complex silhouette that defies definition. Rejecting simplicity for complex geometry, the Theatre is a visual marvel: a multi-faceted prism and a facade constructed with an irregular pattern of triangles and trapezoids. The exterior appears to be covered in a metal mesh – a clean grey that suits the rest of the resort’s amenities while still standing out.

It is, in simple words, stunning. But while it looks like there’s nothing “simple” about the Theatre, at its base is a series of simple decisions and pieces that come together to create something special.

The Dark Horse is in the Design

Albert Marskamp, Vice President of Engineering and Detailing at Walters Group, pulls up a CAD drawing of the interior of the Theatre. “If you look at the outside, it looks complex and crazy,” he says, scrolling through the model. “But, if you take away the paneling and the seating, back to the structural steel...”

The drawing still looked complex, but a clear shape magically appeared in the centre: a stable rectangle. “You can’t see the straight lines anywhere, inside or outside,” Marskamp says. “But they’re there.”

And structural steel is the foundation of that strong central core. “We had long span trusses that are cantilevered out and attached to the solid facade,” explains Marskamp. “And we have hung steel off the structural steel.

“Most structures are supported from below,” he continues. “But with hung steel, the support is coming from above.”

Complex geometries are nothing new to Marskamp or Walters Group’s structural engineers – the company has the Michael Lee-Chin Crystal expansion at the Royal Ontario Museum and the Canadian Museum of Human Rights in Winnipeg on its resume. All of that experience equipped Walters Group for the challenge of building the Theatre.

Getting Set

And it was a challenge. The unique geometry and constraints on the construction site – the cranes had to be erected inside of the building footprint – meant special attention and consideration had to go into the process of erecting the building. “We had four structural engineers, and a dedicated constructability engineer on this project,” Marskamp explains. “Which is not a common practice.”

The constructability engineer’s job was to plan how the building was going to be built. “The engineer of record of the project, they designed the building in its final condition. So you imagine, you put all the pieces together and then turn gravity on, and everything stays up. But most projects don’t work like that.”

Even with the simpler structural “box” of the building, the heavy reliance on hung steel cantilevered outside of the vertical supports meant that Walters Group had to analyze the Theatre in dozens of different stages of construction. “The building is not stable when only half of it is up,” Marskamp says. “And in a lot of cases, you don’t just need the steel skeleton up – you might also need a deck, or the concrete supports in.”

Determining what additional, temporary supports are needed through the construction process was the responsibility of Mike Persaud, Walters' specialty construction engineer.

Covering the Exterior

Covering the structural steel is a layer of 6” thick Noroc-L Insulated Metal Panels, chosen for their noted fire resistance and 100% hidden screws. “These were specific requirements from the client,” notes François Desjardins, Expert engineer – Architectural at Norbec, who supplied the panels. “The Noroc-L panels were the only ones that met those requirements.”

“This project was a bit unique in that there was no separation between the structural steel and the facade panels,” Marskamp explains. “Usually, you have some sort of substructure that connects the two, but in this case the panels were connected directly to the skirt steel.”

Why was this necessary? “6” panels are heavy panels,” says Desjardins. “While they’re not abnormal – IMPs are usually 5”-6” thick – the number, weight, and shapes of them made installing them a challenge.”

“Much of the steel structure was to support the cladding,” agrees Marskamp.

The solution was to devise special connections between trusses and supports where the structural steel joined itself to ensure the panels could lie flush against the skirt steel. “We had more than 1,800 connections,” Marskamp says, doing some quick math. “Not all of those impacted the panel installation, but then you get into these cap connections at the top of vertical supports. You can’t stick out the sides, and you get these torsional loads that are being put on the connections. So, you need a connection that is strong enough to support the cladding while also remaining flush.”

These connectors utilized PJP and CJP welds, which lay flush against the connecting pieces of the steel, as well as some unique structuring. Since the horizontal members were directly supporting the IMPs, the vertical members were able to be set back, allowing the overall structure to be flush.

Even still, the complex geometry and the unique angles and pitches of each surface added new forces to account for. “The connection design of the skirt system took almost as long as the connection design of all of the rest of the building, which includes your primary structural system,” explains Marskamp.

“But this is what we’re good at, and what we love doing.”

How to Build a Complex Building

So, with so many complications and unique features, how do you actually move into construction? “There aren’t any sleepless nights looking for the one solution to the problem,” says Marskamp. “Because there isn’t just one way to do things. You look at the problems, you create a plan, and then you execute on it, making adjustments as needed.”

Marskamp related the construction process to the recent Olympics races. “We had a tight turnaround on this very complex project. Did we start on our predicted start date? Not quite,” he chuckles. “But did we finish on time? Yes."

“They don’t give medals for getting out the blocks first,” he says. “You get gold by crossing the finish line.”

SPECIFICATIONS

BUILDING OWNER/PROJECT COMMISSIONER:

Great Canadian Gaming Corporation

ARCHITECTS:

ENGINEERS:

Walters Group Inc., & RJC Engineers

SUPPLIERS, FABRICATORS, INSTALLERS:

PRODUCTS:

Noroc-L

Interior - Gauge: 26 ga | Colours: Imperial White | Finish: Smooth | Profile: Silkline

Exterior - Gauge: 22 | Colours: Custom Champaign Bronze | Finish: Smooth | Profiles: Micro Rib